- Home

- Marthe Jocelyn

Folly

Folly Read online

Folly

Marthe Jocelyn

FOR MY DAUGHTERS,

HANNAH AND NELL

MARY 1893 Telling

I began exceeding ignorant, apart from what a girl can learn through family mayhem, a dead mother, a grim stepmother, and a sorrowful parting from home. But none of that is useful when it comes to being a servant, is it? And nothing to ready me either, for the other surprises a girl might stumble over. Let no one doubt that I've learned my lesson and plenty more besides.

Imagine me back then, not knowing how silverware is to be laid out on a table, nor how to swill a stone floor or slice up the oddness of a pineapple; I did not know that tossing old tea leaves on the carpet works wonders toward collecting up the dust, nor how bluing keeps your white things white; I did not know how to write a letter and I had never had one come for me; I did not know

2

what a man and a girl might do on a gravestone when they are crazy for each other; I did not know the heart were like a china teacup hanging in the cupboard from a single hook, that it could chip and crack and finally smash to the ground under a boot heel. And I did not know that even smithereens could reassemble into a heart. I did not know any of this.

This leads to that, Mam used to say. The trick is knowing where this begins and which that it might be leading to.

The kiss may not have been the start of things, but it led straight on to the rest of it, me without the slightest idea--well, maybe the slightest--of where it could end up. But one thing is certain: I were as ready for that first kiss as a girl can be. My hair were clean, my neck were washed, and my heart were banging away like a baby's fist on a pile of dirt.

That's jumping ahead of things, so I'll go back and tell what I do know--before and after the kiss, since we won't be hearing anything from Mr. Caden Tucker, will we?

Caden Tucker--scoundrel, braggart, and heart's delight. He'll never be seen again, not ever, so don't you waste your time. The officers claimed they couldn't find him and neither could I, for all I looked till my bosom would split with holding the ache. He'd have nothing to tell you that I can't, that I promise. He were

3

cocky, but he weren't one to rely on for a true story, as it turned out.

I'll confess there were a part of me that shone bright in the sunshine cast by Caden Tucker as it never did elsewhere. A part of me that were me , the true Mary Finn, when I were walking out with him.

4

MARY 1876 Telling About Home in Pinchbeck, Lincolnshire

Our dad had his vegetables, grown for market or trade, or else he planted others' gardens. Winter times, when the ground were sleeping, he'd cut firewood or dig privies or whatever were asked for. Mam were kept busy with us, and the house, but we all helped, as a family does, you know. Though I suppose you're not familiar with the workings of a family.

We went each week to St. Bartholomew's, me taking the boys out to the graveyard when the sermon got them twitching.

"How many now?" I'd ask, and they'd tear up and down the rows, tapping the tops of each stone, shouting out the numbers, not thinking about Sunday or stomping on bones under the grass. But then it were Mam who

5

changed the count and the game weren't so merry anymore.

Mam had four of us before birthing Nan, fifth and last. Mam died a week later, leaving me, just turned thirteen, to be mother as best I could. Until our dad went and found that Margaret Huckle a year after and put her in Mam's bed, thinking he were giving us a present somehow. Really it were like drowning nettles in the bottom of our tea mugs so every time we swallowed there were a sore patch, a blister, hurting deep inside in a way that couldn't be soothed.

That were the kind of talk that would have got me thrashed if anyone heard it, so it stayed quiet, right?

It were me, then Thomas, Davy, Small John, and the baby. Tall John Finn being our dad, meaning the one named for him could only be small.

Now, come Sundays, Dad said Thomas and Davy were big enough to stay plunked in the pew with him, so it'd be Small John and Nan in the churchyard with me. John were always coughing, not eager to run around. I devised other games for him. We picked out the letters on the stones, me knowing how to show him that much.

"Here's an A ," he'd shout. "I found a B !" And after a while he made sense of the words.

"Crick!" he'd cry, or " M for Mason!" and I'd know he were right because Walter Crick were dead from pneumonia and Pauline Mason were the butcher's wife who died from a lump in her neck that stopped her swallowing.

6

Mam's stone were small next to some of the others, about the size of the church Bible, dawn-gray granite with pink flecks, traded for a year of potatoes.

Mary Ann Boothby Finn ,

it said.

Wife of John

A Mother on Earth

An Angel in Heaven

b. 1843 d. 1876

Our dad, knowing Mam's favorites, planted bluebells and lily-of-the-valley. Come springtime they flourished so lush and pretty, even after that Margaret Huckle were thistling about at home, that I know he kept tending Mam's stone, though he never said.

I didn't go there often, not wanting to look sappy, talking to ghosts. I were leery too, of telling Mam only our miseries, so I'd wait till I had other news.

"Thomas lost another tooth," I'd say. "He looks a right fiend, pushing his tongue through the front, with his eyeballs crossed over. And Davy, he might be one of those Chinese monkeys that came with the fair, the way he jumps on chairs and swings about on gates...."

Then I'd come to Small John and the worries would start. "He coughs, Mam, all night sometimes, though I

7

make a warm garlic plaster like you showed me. I don't know if ... well, I just don't."

My hands would go numb with me praying so hard she'd answer. I'd take a two-minute scolding if it meant she'd be there for two minutes. But the swallows would swoop, and the sun would sink, and the evening would sound hollow as an old bucket. The weight of things were on me alone. Along with our dad, of course.

I wonder now what you'd think of him, he not being like any man you've come across here.

I were little mother and he were keeping us fed and covered, strapping the boys when need be, but also telling stories at bedtime. During the day he were a grumbler, barely having enough words to finish out a sentence. But evenings, the boys would call, "Tell us one!" and in he'd come, and set at the end of the mat, with all of us tumbled together in the dark.

"It were a wild night," he'd start in a whisper meant to give us the shivers. "Rain so fierce it came down sideways. Lightning crackled like fire in a giant's grate, and thunder snapped.... There were such a blowing and a dashing of the rain, those poor travelers huddled like lost sheep beneath the lowest branches of an ancient evergreen...." He'd let us picture the turbulent heavens, and the shadowy figures, and the damp needles scenting the air with earth and pine.

"Go on," we'd say. "Who were they?"

"Well," he might say. "It were the young Lord Thomas

8

Fortune and his servant Davy the Eager." Or, another time, "It were a boy named Bold Johnny with his magic puppy, Nana." Small John would push his best two fingers into his mouth with a happy smack, finally the hero.

Or, "It were the peasant lass, Mary, caught out in the storm, ever waiting for her father, lost while struggling home from a great battle against the Viking marauders...."

Even if we'd had a nursery like I saw later in London for Master Sebastian, even if we'd had a whole bed each, we were used to each other's poky elbows and chill wee toes. We liked it best listening, and then sleeping, in a heap.

We'd have been content, going along like that, even without Mam. It were the arrival of that Margaret Huckle t

hat were the next blow, like a tree through the roof.

I don't know how long our dad had known her or where they'd first met, sly-wise, but how I heard were like this:

"Mary." The boys were down at night and I were trying to mend Davy's shirt where the pig-nosed bully Ben Crick had torn it in a tussle at school.

"Yes, Dad." I bit off the thread.

"I've something to say will change things. Ease things for you."

I looked up, catching a whiff of peculiar.

"Since your mam died," he said, "you've been mother to the baby and Small John. And I thank you for it."

A shiver tickled the back of my neck, telling me Watch out! I'd never been thanked yet.

9

"But it's been more than a little girl should do," he said. "You've already got smudging under those bonny green eyes ..." Him calling me bonny ? Now my middle were apple jelly inside.

"I've found a woman who will be my wife."

"Your wife?" I repeated to be certain.

"She's a widow, losing her cottage near the Tumney farm where I go Thursdays." As if that explained. "She'll be a mother too," he said.

"But I'm doing it all just fine," I said. "It were hard when I were thirteen. But now I'm older. I'm better at it. I'll be fifteen next birthday. You don't have to fetch a new mother for us, not now." I could hear my voice go squeaking up. "We don't need a wife."

He patted my hand, lying there, holding the boy's shirt. "Her name is Margaret. Margaret Huckle. She's from over Spalding way. She's been a widow now for about a year. Her husband died, oh, March last, and she needs us as much as we need her."

"We don't need--"

"Think of Nan," he said.

"That's who ... It's Nan, I'm ... Nan's got me ." I tapped my chest. "Me. Since she can't have Mam." But his finger went up, raised like an axe and swung to shush me.

I shook out Davy's shirt, tugged on the collar.

"She's going to live here?"

"I'll bring her for supper one day this week. She can see her new house and meet you all. We'll get ourselves married Sunday next, and have it done."

10

"Sunday next? But that's--" I stopped.

Our dad stood up. "It's your task to make her welcome. I'm off for my pipe." And out he went.

It were none of my business, I knew that. It were our dad, not us, who'd be sleeping next to her. But there were a lump in my belly like a week of cold porridge.

Wednesday came along and Dad said, "I've asked Dick Crebb for an old hen. If you'll make your cock-a-leekie, that'd be a fine way to show Margaret how we've been looking after things up until now. Tonight's the night."

Milk slopped over the lip of the pitcher while I poured into the boys' bowls.

"Spill," said Small John.

"Dress the chicken nice and make those potatoes with the crispy bits. She'll like those."

Small John's fingers stole to his mouth.

"Yes, Dad." I nodded while I were thinking up curse words.

So I went by Crebbs' after I'd walked the big boys to the schoolhouse, with Nan in my arms as always and Small John's fist dragging on my skirt. We collected the hen and I were relieved that Mrs. Crebb had plucked it.

"Maybe she'll be a jolly one," I whispered to Nan. "She doesn't have to be a disappointment. Maybe she'll know how to sew right, or make junket pudding that firms up proper. Maybe she'll sing, or say stories we haven't heard."

11

Maybe she'll be a mother , I thought, which only seems daft now. But not knowing yet, I could still wish. Maybe she'd help with the chores of having five children and there'd be a sliver of each day all my own.

Ha. Not ever did that happen until I were as alone as a soul can be and there's a lesson for you. Don't go wishing for what you know nothing about.

12

JAMES 1884 Home with the Peeveys

James was sick to be going. His whole six years of life he'd been waiting; they'd all been waiting, years. That was what happened to foster children. They had to go back when they stopped being little. But he didn't like it, not one bitty bit, however much they said it would be a new adventure . James didn't like adventures. Not then, and not later when he'd had a few.

"You'll be an explorer," they told him, but he knew that explorers met bugs and beasts and cannibals, so they couldn't trick James.

He didn't like new, he liked the same.

He liked the same he could keep account of.

13

ITEMS GOING WITH HIM:

1 shirt

(He did have a second shirt, but Mama Peevey thought it wouldn't be wanted, so it was left in Kent.)

1 pair of trousers

1 pair of shoes

A cap

(He'd be wearing all that, so did it count as being taken?)

A Bible (from the Reverend Kelly, that he'd never looked at, but he carried it along in case the Good Lord was watching. Maybe a Bible would show them at the Foundling that he was a good and honest boy, though he was pretty certain it was a sin to fib about being honest. He'd felt the strap from Mister P. often enough for what was called devilment, and he knew he fell short of being good, no matter what Mama Peevey said.)

2 whistles, cut from willow by Mister's hand

2 pencils from the shop and an account book, Mister knowing he liked to keep account of things

2 peppermint sticks from the shop, his favorite. Mama Peevey slipped him a peppermint or a butterscotch on a rainy day. "Sugar is always sweet," she'd say. "But 'tis sweeter when the sky holds trouble." He remembered that .

CHILDREN OF JOAN PEEVEY AND

HER HUSBAND, MISTER FRANK PEEVEY:

Arthur Francis Peevey, who died as a baby

Himself, James Nelligan

Elizabeth Ellen Peevey, called Lizzy

Rose Frey

14

Joan Peevey never claimed to be his mother. She was nursing Arthur and had milk to spare, so she took James on from the Foundling Hospital and nursed him too. Lucky thing, she always said, that the left-behind babies had women like Mama Peevey who could feed more than one. Then she bore Lizzy, her own, and fetched Rose, a foundling, because she'd shown the hospital she was good at fostering.

"The good Lord saw fit to take Arthur before he'd got his teeth, but that only left more room in my heart for you, didn't it, lovey?" she said to James. "When you try me like this, I tell the Lord you're being naughty enough for two boys. But really, you mean to be good, don't you, Jamie? Aren't you a good boy?"

This was after she'd cut off Rosie's hair because of him. He'd got boiled sweets from the shop and tucked them into Rosie's braids, to see if the colors would glimmer through like jewels. But they got stuck, right close to her scalp. Mama had tried with vinegar, but finally had to snip them out, Rose howling till her face went purple.

"Aren't you my good boy, James?"

Nodding didn't make it so.

"It's only hair!" he bellowed at Rose. "It'll grow again!"

He liked the shop best, where they played, and where he did his letters and his counting. It wasn't a real shop, like the butcher or Gibson's Bakery. There wasn't an awning, or a proper window. Mister Peevey put up shelves in the front room of the cottage, banging all up and down the walls,

15

and shouting Damn Jesus when he banged himself. The coin box sat on a counter next to the stack of brown paper and twine for wrapping up packages.

Mister noticed early that James liked to count and to put the rows straight, so he set him a task each day, keeping records of the stock.

WHAT WAS IN THE SHOP:

Barrels of pickles and brown sugar and flour and rice

Bottles of vinegar, bottles of bumpy relish, called "gentleman's," black sauce with too many letters called "wooster," red sauce called "piquant," and so many others, all different colors, Mister said to pour on flavor when the meat was boiled tasteless

Matches, candles, lanterns that need dusting, but only by Mama P., her not trus

ting children with glass

Rope, knives, hammers, and mallets--the villain's cupboard, James called it; no swords, but several boxes of poison for killing rats

Ink, nibs, pencils, sealing wax, twine, and all what was needed for accounts or school or packages

Sewing needles, spools of thread in every color, buttons, in sets of five or eight, stitched to painted cards that had gilt titles like: JUST THE THING! or LADIES' LOVELIES.

Pins for sewing and pins for hair, nets and clasps and curved combs made from the shells of tortoises. James hated those combs, thinking of naked tortoises, until one day he sneaked them out and snapped each of them in two. He hid the pieces in the dirt next to the garden steps .

16

Packets and packets of biscuits, oh, and the best thing! A whole row of huge glass jars, with lids too heavy for James to shift by himself .

INSIDE THE JARS:

Peppermint sticks

Toffees wrapped in gilt twists

Sugar mice

Licorice sticks, like rods of tar

Boiled sweets, like lumps of ruby or emerald in a pirate's cache

SOME FIRST WORDS

Peek Frean Ginger Crisps

Hill, Evans & Co. Malt Vinegar

Original and Genuine Lea & Perrins'

Fry's Cocoa

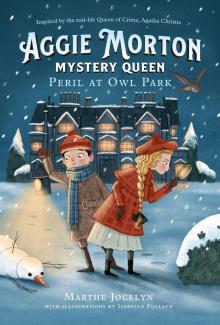

Peril at Owl Park

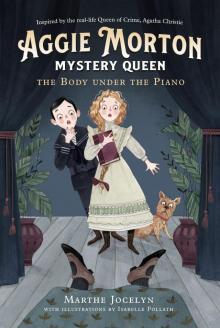

Peril at Owl Park The Body under the Piano

The Body under the Piano Mable Riley

Mable Riley Earthly Astonishments

Earthly Astonishments How It Happened in Peach Hill

How It Happened in Peach Hill The Invisible Day

The Invisible Day The Invisible Harry

The Invisible Harry A Big Dose of Lucky

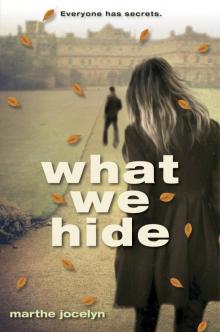

A Big Dose of Lucky What We Hide

What We Hide Would You

Would You Secrets

Secrets First Times

First Times The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Enemy Folly

Folly