- Home

- Marthe Jocelyn

Mable Riley Page 2

Mable Riley Read online

Page 2

My first appearance in a newspaper! I shall keep it here as part of my record. Perhaps someday I will perform some further deed of note.

I did my duty and wrote to Mama and to Hattie, also, relating every moment since our arrival. I did not realize how I miss having a friend until I tumbled out my heart to her on paper. It seems many days more than four since waving our handkerchiefs as we drove away.

Our life's adventure began the moment when we faded from their sight, but what did that hour bring for them? Being up so early to say farewell, none of them would have slept enough. Bea was crying and likely Flossie started, too. Teddy would try to be a little man but could not last, I'm certain. Mama was no doubt left with three sobbing children and one big Arthur to fill with oatmeal before he went to the orchard. I hope Mama is not too lonely without us. Perhaps our absence will make her sad again for Father, just when she was becoming used to his being gone.

We have come upstairs now to retire. Viola has decreed that I sleep on the side of the bed under the window. She thinks it a hardship not to sleep above the chamber pot. I do not use the pot in the night, so I shall not suffer. I will wake with chestnut leaves before my eyes and be happy for it.

Tomorrow is the first day of school. If the air is cooler, I'll wear the blue shirtwaist as it advances my eyes. I wonder what the other scholars might be like. Will Henry and Joseph Brown be there? Perhaps there will be a friend for me, since Elizabeth does not seem likely to fill those shoes.

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 3 FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL!

Viola is asleep already, tired from the rigors of her first day of lessons and the responsibility loaded upon her shoulders. I may not keep the light burning too long but must tell a little of our day.

We arose before six to wash and dress, ready to eat with our hosts at half past the hour. I believe that Viola was nervous. She fussed and fumbled so much that it was I who fastened her buttons. As for me, there were bats learning to fly inside my stomach too!

Elizabeth arrived, commanded by her mother to escort us to the schoolhouse.

Alfred was as good-humoured at dawn as he was at dusk, tugging at my braid and calling me “Teacher, miss.” Viola snapped at him not to encourage me to think above my place. He turned quite red and stopped at once. “He was teasing, Viola,” I said.

“You're to address me as Miss Riley when in the company of your fellow pupils,” she said to me, prim and tight mouthed.

“But Alfred is not –”

“Elizabeth is.”

“I am more like to call you Bossy Boots,” I grumbled.

“Will you begin the day with a detention for disrespect?”

“I think you can make an exception outside the classroom,” said Mr. Howard Goodhand, pulling on his boots. “None of us need scolding in our own kitchen.”

Now it was Violas turn to flush, and what pleasure it gave me! I smiled at our host, realizing I had not done so before. He is quite fearsome looking, with eyebrows that might be planted there like a healthy crop of rye across his forehead. His opinions are firmly stated, and they provide the law at the Goodhand farm. (If his wife occasionally disagrees, she is wise enough not to say so in his hearing.)

Viola is accustomed to discussing things with Mama, and she chafes at Mr. Goodhand's “absolute monarchy.”

V. and I tidied in silence and put our lunch in pails to bring with us bread, cheese, and pears provided by Mrs. Goodhand. Elizabeth walked ahead, with her nose sniffing the clouds.

The school is very pretty: gray-painted board and batten, trimmed with black. There are two enormous oak trees in the yard beside. It is quite a new building, perhaps a dozen years old. Before that, school was taught in the church. Viola says she's blessed it's so nice her friend Carol Anne, from the Normal School, is in a schoolhouse with cracked walls and a leaking roof! Ours has four windows, a good stove, and a little platform at one end for Viola's desk to sit up on.

Miss Riley kept me busy dusting the schoolroom for the arrival of her scholars. The best of my morning duties will be to stand on the top step and ring the brass bell to alert every scholar, cow, and rat within two miles that lessons are beginning.

I was surprised to see my new schoolmates form a line so promptly upon hearing the bell; the previous master must have trained them firmly to make their manners. The boys bowed and the girls each curtsied, from the littlest up to Elizabeth. It was this parade of respect more than anything else, I think, that made Viola believe she is now a teacher!

As soon as all were assembled, we said the Lord's Prayer and then Viola took roll call. There were sixteen scholars today. Only two were missing from the registration list. Viola says we had so many because it is the first day and all the children wanted a peek at her. We will not expect such good attendance during the early autumn months when the farms are still so busy and needing “all hands on deck.”

There are four of us in Grade Eight this year: myself, Elizabeth, a Mennonite girl named Adeline, and a boy named Tommy Thomas.

Tommy is a funny boy with big ears and crooked spectacles. He knows the answer to every question posed. Adeline is very sweet and demure, dressed plainly in the custom of the Mennonite people. She will not take the examinations. She says no one in her family has gone to school past the age of fourteen. She will work on the farm and have no more need of book learning. I cannot tell if this makes her sad. If I had no books, I would shrivel up like a dead caterpillar.

The Brown boys alone make up Grade Seven. I had no occasion to speak with them today but have identified their differences. The gap between Henry's front teeth is slightly greater than his brother's. He also has an extra freckle at the corner of his left eye.

There are six long tables for the scholars, placed in three rows. The early grades sit in the front and the older ones at back. The boys sit to the left of the stove and girls on the right. Today I sat with the little ones, though it will depend upon the lesson where I am each hour. Irene is my smallest and cried for her mama all through the morning.

Viola did not drive us hard today. She tried to discover what the pupils had achieved last year in each of the subjects, as she took us through the daily schedule:

Arithmetic

Grammar and Spelling (alternating with Penmanship and Recitation)

Geography or Science

Lunch Recess!

Reading and Latin

Drawing, Music, or Sewing to end the day

Except on Fridays: Spelling Bee!

As soon as Viola had announced the routine, an urgent hand shot into the air.

“Cathy Forrest?”

“We are accustomed to arithmetic after lunch, Miss Riley.”

“I believe your minds are sharper in the morning,” said Miss Riley.

“This will not please my mother,” said Cathy Forrest.

“Then she had best not attend Grade Five at Sellerton School,” said Miss Riley. “Shall we proceed?”

Ha! I thought. Winning point to Miss Riley.

The trick was played at lunchtime.

We all went outside to eat our lunches in the yard and to catch a last whiff of summer. Miss Riley came with us, though I suspect that Mr. Tamblyn, her predecessor, had never done so.

When she folded back the napkin on her lunch pail, there curled a garter snake, gleaming green against the wedge of cheese. She dropped the pail, and the snake wriggled out across her boots while she struggled not to scream. (Lyddie Thomas and Cathy Forrest, however, squealed loudly enough to wake snakes from here to Toronto.)

The shuffling laughter stopped while we all held our breath. What would she do? (If it were I who had put a snake in her lunch, Viola would have yelped and pinched me, but she knew this was a test.)

“There is something you should know about me,” said Viola, speaking very slowly and softly, the way our mother does when she is most tried. I think I was the only one to hear the wobble in her voice. The other scholars leaned closer to hear each word.

“This is my fir

st year as a teacher. Last year I was a scholar. I am well aware of all the tricks that scholars like to play. I may be different from Mr. Tamblyn, but being a woman does not mean I will not use a leather strap or the cane. You have been warned.” She examined the faces around her, encountering so many blushes and shifting eyes, she could not possibly identify the true culprit(s).

“One other thing,” she added. “I am a country girl. Snakes do not alarm me.”

Liar, I thought.

“Nor do frogs or beetles or toads. And do not imagine that I will excuse you because it is the first day of school. Since no one cares to accept responsibility, all of you will write lines tonight. Now, go and eat your lunch. The bell will ring in twenty-seven minutes.”

I was proud of my sister for this speech. She managed to stay calm (though she never does at home) and to give an impression of assurance, whether or not she felt it.

When the afternoon was over, I believe Viola would say her first day was a successful one. She beat a steady rhythm on her desk as the scholars marched out in single file and watched through the window to see the mayhem of release.

I patted her hand. “Well done, Miss Riley.”

She smiled, grateful that it was over and she still standing!

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 5

Too tired to write. I've had to wash both shirtwaists tonight as well as Viola's, just to be kind, though it did me no good, for she tells me I'm still to check the spelling on all the papers she collected today! And I shall be up early to iron before school.

Mrs. Goodhand is very proud of her new “cool-handle” iron. The handle detaches while the iron is in the fire and thereby stays cool enough to hold with a bare hand! I hope it is not an inconvenience that I will need to heat the iron and use a corner of the table for my board while breakfast is being prepared. Mrs. Goodhand has a disapproving way of folding her lip inside, like pushing a worm back under the earth.

One other thing I must tell I had my first conversation with Henry Brown. It went like this:

Location: In the little cloakroom behind the classroom. Mable sits upon the bench, tying her boot lace before going into the yard to eat lunch. Henry comes in to fetch forgotten cap.

Henry: Oh!

Mable: Hello.

Henry: Uh. Didn't see you.

Mable: Did I frighten you?

Henry: Uh. No. Didn't see you, that's all.

Henry plucks cap from peg and leaves. Mable leans head against wall and sighs.

Not a romantic encounter, perhaps, but a beginning.

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 6

I have realized in only one week of lessons that to be a teacher is tiring work. There being eight grades at Sellerton, Viola must compose eight lessons for every subject every day. When she teaches the same lesson to two or three grades at once, the results must be graded with different expectations. Her organization is impressive as she plans her roster. If the Grade Threes and Fours are practicing their penmanship, the Grade Fives and Sixes are memorizing Scriptures or poetry and the Grade Sevens and Eights are reciting their passages. Then all must rotate and attend the other tasks. For every grade, history and geography are different lists of dates and battles and kings and lakes and mountains and towns, each to be memorized and recited. Arithmetic is the most complicated of all.

All this labour does not excuse Viola of her ill humour, for she has possessed that always, but it excuses me from lengthy entries in this journal at the end of a school day. I promise to catch things up at the weekend, for this evening I had an assignment to fulfill. Viola requires us (from Grade Five up) to compose a poem about our family….

ODE TO THE RILEY FAMILY

The firstborn is Viola

Known to you as Teacher dear.

You call her Miss,

I call her Sis,

And pray for her good cheer.

Arthur is our steady one,

His mother's helping hand.

He seldom rests,

But often jests

And is a drummer in the band.

How shall I say who I am?

I'm Mable, third in line.

I read, I write,

Dream day and night

Adventure shall be mine….

Flossie is the clumsy one,

She stumbles through her day.

But she is best

At the Hug Contest,

And wins my heart that way.

The six-year-old is Teddy

Though he'd have us call him Ted.

He tries to please

But likes to tease

And fights off going to bed.

And who should be our baby,

Though she is grown past three?

Her face is round,

Her eyes are brown,

She is our merry Bea

Viola need not know I wrote a second verse about her, for it certainly cannot be published:

Viola is a viper

Whene'er she speaks, she stings.

If ever she

Were nice to me

A Heavenly choir would sing!

Ambler's Corners

September 5, 1901

My dear daughters,

How strange that I am writing to you two hundred miles away! That you will read my letter in a room I have never seen, that already you have met people whom your very own mother will never know. Yet how proud I am that you both have the courage to make this true. I'm not certain I would have had the same spirit at your age. Of course, getting married at sixteen and having you, Viola, the following year, changed my dreams from adventure to mothering.

As you encounter a new world, be comforted that life at home has not changed except that you are not here, my darlings. (I am not yet used to that.) Bea especially does not understand where you have gone. “Where my Maybe?” she asks a dozen times an hour, hunting Mable high and low.

Flossie has taken to sleeping in your bed, thinking herself very brave because of the extra height.

Arthur has begun to pick the back trees, the apples before the pears. He has William Foster to help and a boy from Newtown. Teddy pleaded to work on Saturday and was very pleased with the nickel I paid for his two bushels.

I must patch Teddy's trousers before I pick the peas for supper, so I will sign off for now.

Thank you for writing to tell me how you've settled. I am so proud, as I know your father would be also.

With many kisses,

Your loving mother

Ambler's Corners

September 5, 1901

Dearest Mable,

It comes to me twenty times in a morning that you have moved away. I had only begun getting used to it when your letter arrived and I missed you all over again. How can I bear a whole year apart from you? I implore you not to find another friend while you are gone. All the girls at school are missing you also. Lunch hours are not such fun without you telling stories. I wish you would write some down and send them to me that I may entertain the girls on your behalf.

And it's not only the girls who mourn your absence! Mr. Gilfallen remarked that he would miss your presence because of the blessed quiet in the schoolroom. Jimmy Fender moons about like a lamb who has lost his tail. Naturally, we tease him for this because he gets so very flustered. His ears twitch at every mention of your name.

As for the dashing Brown boys, it seems I am not to trust you to show prudence when a handsome face (or two!) is at hand. Without me at your side to rein you in, your high spirits will perhaps carry you to dangerous places. Please recall yourself on my behalf. And remember that your sister will have no cause for complaint if you are devoted to your studies and other duties.

Our pleasure should come because of our goodness, not in hiding from it.

Please write as soon and as often as you have a penny for postage.

Fondly, your true friend,

Hattie Summers

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 7

There is terrible news from the United States. Mrs.

Goodhand has been wringing her hands since we heard. President McKinley was shot yesterday while attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York.

The man who did it was an anarchist who gave an assumed name, though it is discovered that his real one is Leon F. Czolgosz. (There is no instruction in the newspaper as to how that name is pronounced!)

The Stratford Daily Beacon declares that the president's wounds may not be fatal. But Mrs. Goodhand says that the particulars of his operation may prove fatal to many a sensitive reader. The newspaper clearly explains how one of the bullets penetrated the abdomen five inches below the left nipple and how a search was made for the exit in the back wall of the stomach, and many other details that are distasteful to dwell on. I find myself reading each account with close attention, as if greater familiarity will alleviate the horror.

Here, it is raining in such torrents that there can be no suggestion of a walk. The cows are hunched together under the trees and seem to be wearing black mud stockings. It is the weather, as well as the poor president, making me feel so dreary, on top of a scolding from Viola and wishing for home.

As crowded as we were in Ambler's Corners, I preferred sharing my room with Flossie and Bea than with Viola, who appears to fancy herself my mother now that we are away. But even our mother left me more to myself, having all the others to mind and mend. V. has only me to bully. My crime to-day was to use her hairbrush! Mine seems to have been abducted by the chestnut tree, for it is nowhere to be found. It cannot be good preparation for a steady demeanor in the classroom that Viola uses hot words over such a small offense. She would be better suited to herding cattle, perhaps, or scaring crows!

Since it still is raining, I shall begin a story to send to Hattie, full of romance and adventure….

A Romantic Novel

by Mable Rosamund Riley

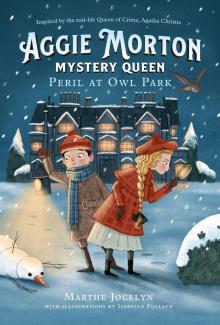

Peril at Owl Park

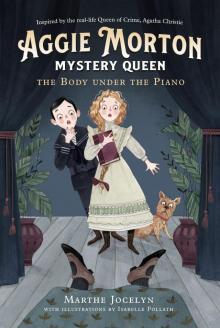

Peril at Owl Park The Body under the Piano

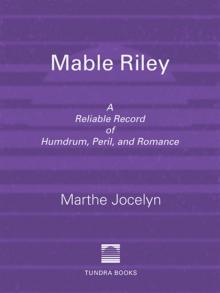

The Body under the Piano Mable Riley

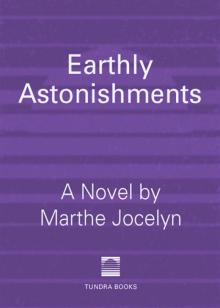

Mable Riley Earthly Astonishments

Earthly Astonishments How It Happened in Peach Hill

How It Happened in Peach Hill The Invisible Day

The Invisible Day The Invisible Harry

The Invisible Harry A Big Dose of Lucky

A Big Dose of Lucky What We Hide

What We Hide Would You

Would You Secrets

Secrets First Times

First Times The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Enemy Folly

Folly