- Home

- Marthe Jocelyn

Secrets Page 4

Secrets Read online

Page 4

But then I overheard it again. Was 5-G called that by all the kids? What did they consider garbagey? The guys like Stooge who were repeating? The kids from other countries? The room we’re in? None of those were good reasons. But what if that label stuck to me?

I wanted people to point at me for good reasons.

The main thing – okay, maybe the only thing – that I have going for me is being able to draw. At my old school, I was best known for a mural I painted on the wall of the stairwell. I thought maybe I could try that here.

But not on a wall. Because, on my first day here, I told my mom, “The place is falling apart! They should tear it down!” Then, on my second day, they announced that they were demolishing the entire school as soon as term was over. They’ve already started hammering and bashing at the portables in the playground. Not because of me, just a coincidence.

The demolition art project, though, that was because of me. This is how it happened.

The wreckers started putting wooden hoardings around the school to keep people away from the rubble. To anyone else, hoardings look like big plain sheets of plywood. But, as soon as I saw them, I thought, hey, that’s where I could paint. Something fabulous and noticeable, one or two panels at the entrance to the school. In extra-high-gloss paint.

I suggested to Miss Goatherd that the school’s neighbors would rather look at art than at plain plywood. I could imagine my finished panels photographed for the local newspaper. After the demolition was over, they’d pry them off the fence, frame them, and keep them at the Board of Education office. I bet they’d offer me some kind of prize.

“Wonderful!” said Miss Goatherd. “We’ll have a grade five mural project!”

Rats.

She blathered on. It could come under the Peer Partner Cooperation Whatsit Something Program, she said.

That was yesterday. Today we’re supposed to start. Each team will paint one panel, about the size of two regular doors side by side. We have the whole twelve days till school’s out. I guess Miss Goatherd is as sick of reviews as we are.

My partners are Androullah Mortzopoulos and Lizzie Nelson. I do not want partners. I want to paint alone. I don’t want to get all chummy and close with girls I hardly know. Not now.

The morning bell clangs hysterically, like it’s taking its last breath. Miss Goatherd is rummaging in the cupboard. Kids are jamming themselves through the door of 5-G, just what I’m at my desk early to avoid. I keep a lookout for Androullah coming in. There she is. Androullah has so much hair, it fills the doorway of 5-G, like hundreds of curly black telephone cords sticking out every which way.

“Heyyyy!!!” comes an angry shout from behind her. Ah, partner number two – that small but mean girl, Lizzie. “Move, you!”

Androullah jolts forward and the telephone cords wave around like tentacles. Lizzie never gets caught. Only a teacher hanging from the ceiling could actually see it happen. Androullah doesn’t get mad, though. She only started here two weeks ago. Why would someone come to a new school for the last month of classes? I bet she’s been in some kind of trouble. Looking at her, I’m guessing it was interesting, cool trouble.

She makes a melodramatic sweeping do-come-in motion, as if she’s Lizzie’s doorman. Ha! laugh the kids who see it. They’re right on the verge of a yell-fest when Miss Goatherd backs out of the supply cupboard. A boxful of pink erasers falls out with her and they boiiiing all over the floor. The room shakes with the noise of jackhammering outside, and a few flakes of plaster float down from the ceiling. Fake snow in this June heat wave.

“Settle down, people,” says Miss Goatherd several times, tapping the tips of her fingers together. As a noiseless clap, it’s so effective the yelling drops one percent.

“Morning, Miss Gauthiere,” singsongs Androullah, pronouncing it extracorrectly She doesn’t care about the snickers. Androullah glides over the kids picking up erasers and floats down to her desk as smoothly as someone on TV. Her T-shirt today, big enough for three scrawny Lizzies, is bright purple. Her canvas backpack has black Magic Marker drawings on it, ones she’s done herself. In my old life, I might have tried being friends with someone like her. Not now, though. Androullah is very bouncy. Exactly the kind of person who’s bound to ask personal questions when you least expect it.

Miss Goatherd does one last morning of math review. One thing I like about her class is being allowed to doodle all the time. Miss Goatherd’s theory is that you can actually learn more from a lecture on desert plant life, fractions, or even French verbs, when you’re doodling and your Right Brain is busy. Or Left Brain. I can never get them straight. Which might say something about my own brain that I don’t want to know.

I turn sideways to watch Lizzie and Androullah, first one way and then the other. I bet they make the sides of these plastic seats sharp on purpose. They order the factory to manufacture seats guaranteed to keep every grade-five behind facing front. If behinds can face front. I laugh inside at my own joke and ignore where the seat is making permanent dents in me.

Lizzie isn’t doodling. She’s covering each page of a large notebook from top to bottom in solid black. When I first got here in April, she was about three-quarters of the way through the notebook. Now she’s almost at the end. Lizzie’s constant bad temper makes me very nervous. I have enough of that at home.

Androullah is drawing, not doodling.

Just before the recess bell, the PA system comes on, crackling and hissing. I’m being called to the office.

I rush down the hall. My mom’s on the phone, something about the counseling session with my dad getting moved so she’ll be late picking me up. We’re supposed to go buy stuff for our crummy, tiny, ugly apartment. I hate this, wondering if we’re ever going back home. Wondering if we do, will the arguing go on? Why did it start in the first place? Tears press sharply against my eyes.

Back when we left, I asked my mom why. “It wasn’t that bad,” I said.

She told me she’d hidden the really bad parts from me on purpose. I couldn’t believe they were fighting even more than I knew. It made me furious in two ways: first of all that they did it, and second that they kept it a secret.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I shouted.

Her answer was firm and matter-of-fact. “I don’t have to tell you everything.”

Now, I try to keep my mom on the phone, but she’s been able to hear both bells – the one at the start of recess and the one at the end. She tells me to get back to the classroom.

I wish I could say that to people, I don’t have to tell you everything. I feel obligated to answer questions. I don’t know why. If I could sound as cool and confident as someone like Androullah, no one would be nosy with me. Even if I said it prickly and bad-tempered like Lizzie, it would be better than babbling on. I’d like to be the kind of person who doesn’t babble on.

But I’m not. In May, after I’d been here about a month and didn’t speak much to anybody, I was in the school library one afternoon. My mom and dad were crowding my brain and I was feeling pretty blue, so I hid out in TEEN FICTION H-M. This girl, Kathryn, from 5-A headed over and said hey, hi, are you okay, you’re new here, right? I thought I could answer casually, but my voice came out way too high and gaspy It was like the top coming off a warm bottle of pop that’s been rolling around in the car. Suddenly I was fizzing on about how I couldn’t get used to it here, how my other school was great, how really happy I was there, except that my parents think arguing is an Olympic event they have to constantly train for. My eyes started dripping. I took a breath, but continued even faster: how it got really bad and then worse, how my mom and I moved to this apartment on Wendell – it’s horrible and I don’t know what’s going to happen. Then I said sorry, sorry for crying. And somewhere in there I think I told her my name, wrong, and finally, finally, I sputtered to a stop.

All this talking had backed up inside of me. Rule out secret agent as possible career choice. If a stranger had done that to me, bawling away in the back o

f the library, I’d feel like a dope trying to think what to say.

Kathryn, however, stared at me with her eyes wide-open and completely still. She didn’t blink. Probably didn’t breathe. In spite of the fizzing, I thought this was a very cool way to avoid saying anything and made a mental note to try it out sometime. I couldn’t tell if she was friendly or making fan of me. I knew she looked disgusted when I told about my parents fighting. Good thing I didn’t mention the time my mom threw the mayonnaise. Or other things. Stuff that might be funny in a puppet show or a cartoon, but not in real life. Not in my life. Stuff I don’t want people to know. Since then I try to imagine that my lips are KrazyGlued together, so I don’t blurt out my life story again.

When I get back to the class after talking to my mom, Miss Goatherd is just finishing her instructions for the mural project. 5-G astonishes me by being mildly enthusiastic. We line up in our teams and head for the gym.

A packet of huge sheets of newsprint has just arrived, donated by the local newspaper. Miss Goatherd instructs us to do lots of individual rough sketches first, then work out our ideas together. After that we’ll move outdoors, put a coat of white primer on the plywood, and paint!

While Lizzie sullenly goes to get pencils and erasers, I tell Androullah, “This whole mural thing, it was my idea, you know.”

“Wow, really?” she says, impressed. And she describes the idea she’s come up with: Violetville, with a pale lilac sky. It sounds pretty good. I imagine all the people wearing striped and dotted purple outfits.

Then Androullah speaks to me in a low voice, “Hey, you want a good art tip?”

I shrug. “Sure.”

“Don’t ever empty a can of paint into your teacher’s purse.”

“What?”

“Unless,” she says, dragging it out, “you want to get kicked out of school and sent off to live with your aunt, someplace where you don’t know any body. But maybe then your teacher would stop dating your dad, don’t you think?”

Wow. I have no idea how to answer. I stare at Androullah with my eyes completely still and wide-open, not blinking. Excellent time for Lizzie to return with our supplies.

It feels wonderful to make huge sweeping pencil strokes on big paper and to work on the floor after months squinched up at a desk. Working alone, that’s the best. I wish it could stay like this. The rest of the room bustles with talking and the crackle of the big sheets of paper. At lunchtime, everybody eats with one hand and keeps drawing with the other. My partners are on either side, but we’re not talking. We’re not being shy, it’s more like we’re way down inside ourselves.

In the afternoon, Miss Goatherd sends the class outside for a break. The three of us start to go in different directions, but she calls out, “Stay in your groups, people. Discuss what you’re doing.”

A couple of the rougher 5-G boys and the two makeup girls push past us, horsing around, hooting and shoving.

“Ow!” I make a face as they strut away. “I do not belong in this class!” I say it low and grumbly, but it must have come out sounding stuck-up because Lizzie glares at me and snaps, “Like I do?”

Maybe she’s bugged by the garbage class label too. Hey, maybe even tattooed, grade-repeating Stooge doesn’t appreciate it.

“It wuzza mistake, Warden,” says Androullah, in a movie-gangster voice, “I was framed, framed, I tell ya.”

We sit on the grass at the edge of the playground to wait out the break time. Lizzie is picking at the dry grass and whining about the heat. I’m so tense I might as well be sitting on broken glass. That’s how Lizzie looks, too.

Androullah suddenly says, very seriously, “Okay, you guys, you probably wonder why I’m here.” She pauses until we both look right at her. “I mean, at the school, so late in the year and everything.”

Ack. I shrink inside. If she tells her stuff, maybe I’ll have to tell mine. I don’t want to. Once I start, who knows how much will come out of my mouth? Also, I don’t want to know what trouble Androullah got into before coming here (let’s face it, I have a clue). I don’t really want to know about Lizzie either, what makes her so angry. Probably it’s something horrible at home. And double probably, she’d clobber me five seconds after spilling.

All I have to say to Lizzie is, there are other colors besides black. All I want to talk to Androullah about is drawing.

But Androullah fools us.

“I suppose,” she proclaims dramatically, “that I can at last reveal this to you both, but it’s top secret. We’re displaced Grecian royalty, my family, the Mortzopouloses, and we must roam from town to town. I’m actually the famous Princessa Androullianna. But I must learn to behave exactly like the commoners. Will you teach me, my loyal subjects? In exchange, I shall let you be royalty too and we will practice our royal deportment together.”

She’s so gushy and silly, Lizzie and I snort in disbelief. There’s a peculiar noise coming out of Lizzie. I think it’s giggling.

“My turn, now!” she says. “Okay, um … all right…. Okay, absolute top secret for me, too. I suppose you’ve heard of the Witness Protection Program? Well, it really works, man. I’m this awesome criminal mastermind, but I’m hiding out with a fake family and going to this rat hole school because nobody would think to look for me here. You gotta admit, this is a brilliant disguise.”

“I don’t know,” says Androullah. “I’m pretty sure Stooge is an FBI informant. What did you witness? Or do? Jewel-thieving? Embezzlement? At the very least, can you reveal to us your real name?”

“Clandestina Von Trillium-Marmalade,” says Lizzie, “but of course, if you tell, I’ll have to have you killed.” I didn’t know Lizzie could be funny.

“Right,” says Androullah, “by Eustace. He’s got the lethal miniflashlight.” And she pretends to whack Lizzie to death using an abandoned Popsicle stick.

Then she turns to me. “Now, Ruthie Naimie, if that is your real namie, tell us the truth and nothing but the truth.” She slips off her sandal to use as a microphone.

Hey, I say to my brain, remember when you used to know how to play along?

“It’s my parents,” I say woefully. “My parents WILL NOT STOP fighting.” I look shiftily from left to right. “It’s ever since we won the fifty million dollars.” I do a fake sob with my voice. “In order to claim it, we must agree on how to spend it. My dad wants to buy a castle in the Swiss Alps and my mom wants –” I pause “– a giant beach house mansion on the ocean, in the middle of the movie stars.”

“What do you want?” asks Lizzie.

“I don’t care,” I say, “as long as half the money gets used to hire lots and lots of servants. Then nobody would ever get mad because the housework, or lawn mowing, or whatever, would always be done.” Boy, that really would help.

“So,” I continue, “I’m temporarily in 5-G to escape the hordes of gold diggers who want to marry me. And, of course, you are both totally invited to come spend the summer at whichever place we decide on.”

Miss Goatherd is calling us back in.

Everybody loves it when it’s time for the painting to begin, even the kids who can’t hold a brush properly. Androullah and I go around showing them how. Some kids are doing just stripes or spirals. Three teams from 5-G and four from another class combined their panels to do an ocean scene. So far, our own panel, Purpleland – we changed the name – is gorgeous.

For Lizzie, Androullah, and me, it’s as if we’ve made a pact without spelling it out in a lot of words. We’re just not going to ask each other certain questions. Yet, anyway. And maybe creative lying, or exaggerating, or just goofing around with a tall story, any of that’s okay. This makes me feel a lot safer. Clamming up is only a medium-good way to sidestep personal questions. It gets kind of lonely.

The three of us talk our heads off. Laughing, joking, and painting, a pretty good combination. I’m not that interested anymore in whether I get known for the best painting.

I think about asking Androullah why, really, she cam

e here. But I don’t.

I start to ask Lizzie about what makes her do the black notebook pages. But I stop.

I don’t need to know.

The Gift

Julie Johnston

“And if I let you go,” Rosalind’s mother said, “you are not to set foot inside that house.” She meant the house where the old women lived. They were aunts of her mother and Aunt Lydia.

Ros had a hazy memory of them – one thin, one fat. “She’ll have to be told sometime,” she thinks one of them said. She’d been almost too small to remember, except that she does.

“I won’t go in their house,” Ros said. “Anyway, it’s miles from the farm. Why would I?”

And so her mother agreed to let her visit her cousin Cornelius in the country for the Christmas holidays. “And I want you to eat every scrap on your plate. There’s a Depression on, young lady. I won’t have you wasting food at Aunt Lydia’s.”

Rosalind nodded. As long as it’s not turnips.

*

And here she was, on the train, alone. The trip took an hour, giving her time to think. Holidays were the only good things about school. No Gertie Goss for over a week. Gertie Goss, her archenemy, called her stuck-up and said stupid things, like “You’ve got a crazy sister!”

“Have not!” Ros called back. “You have!”

“Have so! You can ask my mother!”

Ros had five sisters and not one was the least bit crazy. Beatrice, the oldest, was too pretty for her own good, their mother said, but that didn’t make her crazy. Marietta was brainy and was studying to be a doctor. Vanessa was grouchy and nearly finished high school. And Sylvia and Cynthia, the twins, were … well, twins. There wasn’t much else you could say about them, except that they weren’t crazy, either.

She would be happy to see her cousin Corny. He was bossy, but so was she. They made a good pair when they got together, usually in summer at her place. He taught her to play gin rummy and she taught him to climb trees, even though he was afraid of heights. “Look up to where you’re going, not down to where you’ve been,” she told him. And, sweating, puffing, he would inch upward, his eyes on hers, mesmerized. They were both eleven.

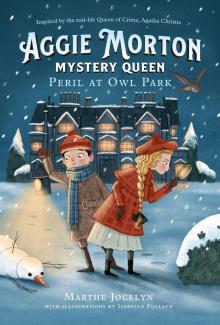

Peril at Owl Park

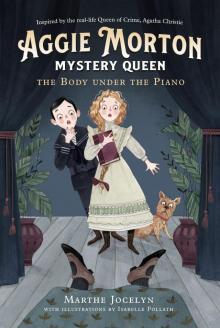

Peril at Owl Park The Body under the Piano

The Body under the Piano Mable Riley

Mable Riley Earthly Astonishments

Earthly Astonishments How It Happened in Peach Hill

How It Happened in Peach Hill The Invisible Day

The Invisible Day The Invisible Harry

The Invisible Harry A Big Dose of Lucky

A Big Dose of Lucky What We Hide

What We Hide Would You

Would You Secrets

Secrets First Times

First Times The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Enemy Folly

Folly